21ST NOVEMBER 2022

RECORD 8 PLANET KIRA ︎

RECORD 8 PLANET KIRA ︎

Imagine you are in the cinema. The room, the smell, the seats. Everything that makes it so magical. We cry, we laugh and feel cathartic in English, Italian, French or any other language. Being tricked the way the characters are by their writers.

Imagine the characters living their lives (quoting Jean-Luc Godard), keep imaginging them screaming, loving and crying. They live not in the frames of the film but across the speed of the running time. Free to make their choices, taking their time for their daily rituals and abstract conversations. Well, sometimes (just like with us) they are also not being heard really or, perhaps, they are not the ones listening either. But they are okay (or eventually will be). That is how you know you are watching Kira Muratova’s film.

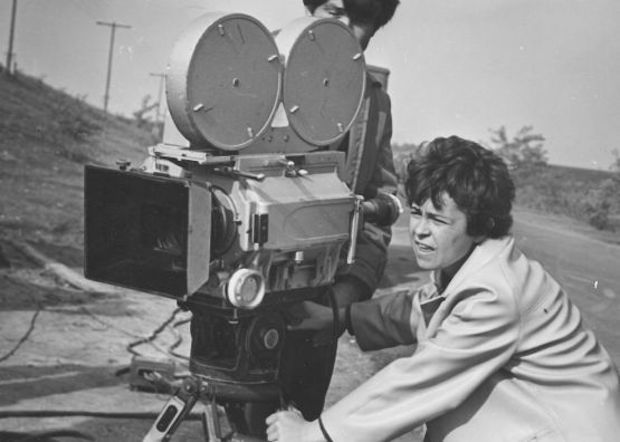

It’s a miracle to catch her films in the cinema, on the big screen (how she had, perhaps, imagined them to be seen). They grew to have their own spot in cinephiles’ hearts quite later than Muratova first started making films. Her debut Brief Encounters (1967), starring a Soviet icon (and a later husband of an iconic French actress Marina Vlady) Vladimir Vysotsky, tells a story of a love triangle, entangling three different spirits within the circumstances of a promising Soviet town. The film was censored and only released again on the screen years later.

The film I went to see at Castle Cinema in East London was programmed by jellied reels, and truly a gem, The Long Farewell (1971). Probably Muratova’s most famous film outside of her home country. The film braids two opposites in the plot, exploring care in the relationship of a mother and her teenage son and the grief of both parting now their separate ways. Following the son’s decision to move in with his archaeologist travelling dad (in some ways having this detail as a loose heritage from Brief Encounters (1967) ), the inevitability that Eugenia is faced with accepting allows the audience to peep between the facets of her reality and the world she builds for herself. Just like Kira Muratova’s other stories, this one captures the glimpses of personal tragedy through little details and motherly gives Evgenia and her son Sasha space to express themselves and be heard by different means.

Muratova’s female characters are not scared of the implied rules of the world they have to live in, they know how to make it their own, which is very prominent and resembling with the stories by the infamous Agnès Varda, Jean Luc Goddard and (let’s move outside France) a Czech film pioneer Věra Chytilová. Despite being an unconventional director in the Soviet times, women in her films adopt some uniform that comes across as a mask and an armour they wear every day, when encountering society.

Muratova was not only adored by film-lovers all around the world but also by her colleagues, remarkable directors Alexandr Sokurov, Andrzej Wajda, Alexei German and Ali Khamraev (among others) that worked across the USSR and Eastern Europe. Her films gained international popularity in the 90s when the director was invited to attend an endless number of film festivals across the globe and was actively interviewed and written about in the press. However, having a life-long journey with her works, Kira Muratova explained her work process and decision-making in a very simple way, reminding us that the freedom of her cinema world had to remain on her rules, and its physics doesn’t need some special justification or reasoning. Perhaps, just like in life, the planet doesn’t ask permission to spin, so Muratova’s films don’t explain the way they breathe; and that’s why it’s hard not to love them and relate.

Yours,

5TO9 FC

Next writing → MARCH